A Ghost Story is startlingly humane given its title. David Lowery’s 2017 film follows M (Rooney Mara) and C (Casey Affleck), a young married couple on the cusp of change. They live in an innocuous little house in rural Texas. The setting is mundane, and almost serene: their house is well-worn and washed in late afternoon sunshine; the interior is cluttered with flea market furniture and books. But there’s tension between M and C. They need to pack for a move, but C is reluctant. He has a soft spot for this house, this place. He’s a musician; he strums his guitar, his face permanently sullen. M is impatient. “What is it you like so much about this house?” she demands. “History,” C responds. Cut to an excruciatingly long shot of M dragging a piece of furniture from their front door to the curbside. Cut to a wrecked car, just a few yards from the house. Smoke rises. C is dead in the driver’s seat.

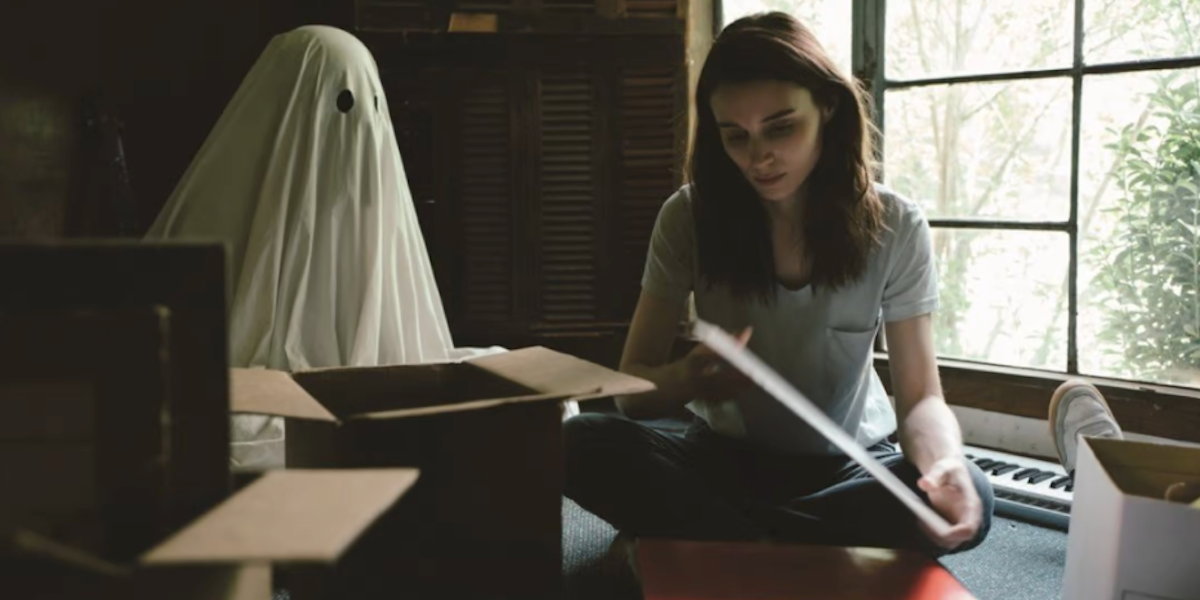

This sounds like a depressing and unfortunate start to a film, and it is. The aftermath of C’s death unfolds in a typical manner: M goes to identify C’s body in the morgue, and after staring at his corpse, pulls the sheet over his face and strides out of the hospital room. There is a long shot of C’s lifeless body under the sheet on the metal gurney. Suddenly, C sits up; he stands and walks out of the hospital. Here the tone of the movie shifts from sad to strange. C spends the rest of the movie silent under his sheet, his emotions conveyed only through dark, sagging eye holes and precise, if limited, body language. Ghosts are most frightening when they’re unseen; ghouls are most terrifying when they possess the bodies of the living. But C’s ghost is a caricature: he is large and cumbersome on the screen, unseen by the people around him but comically obvious to the viewers. He lingers in the corner of frames, dejected. He does not attempt to reach M — she receives no messages from beyond. Yet in contrast with the typical ontological ambiguity of ghost stories, there is never any question about his existence.

There is a strange comfort here. The cartoonish visualization of a ghost exemplifies the movie’s tender and at times irreverent approach to its very serious subjects: the relationships between time, love, and death. C is always nearby, just inches from living humans, chatting with a neighboring ghost. Death doesn’t look so frightening through Lowery’s lens. The childish Halloween rendering of a ghost in the midst of the drama unfolding around him feels like a self-aware choice. Rather than profess to know anything about the great questions of life, Lowery seems to admit that he doesn’t. This approach doesn’t minimize the movie’s gravitas; on the contrary, Lowery’s humility is eye-opening. A Ghost Story tells one story about a tragic young couple, and a much bigger one about the nature of human life — and the latter, the movie reminds us, is an ongoing mystery.

The formal genius of A Ghost Story is in the way that Lowery manages to tell both of these stories simultaneously, carefully interweaving specificity and abstraction. The larger story commences after C’s death, and the film’s form shifts accordingly: after C leaves the morgue, the movie cuts from scene to scene in more abrupt succession without transitions. M’s story creeps along — in a five-minute uninterrupted shot, she gorges on a pie that her realtor dropped off. She is immersed in the slow grind of everyday grief. But C’s ghost has a macro vantage point, and time begins to rush by. M starts to recover, goes on a date. She’s moving out. She folds a tiny note in the living room doorway, paints over it, and is gone. Ghost C, seemingly tethered to the house, watches as a new family moves in, then as the home is demolished, as the neighborhood turns from home to skyscrapers. M is long gone, the movie whirling into abstraction. At this point, C jumps off the edge of a large building only to find himself in the past, at a colonial family’s campsite. From there, time moves forward again, back toward his life with M. Ghost C watches as they move into their house, as all the same scenes unfold leading up to his death. But this time, he knows what to do, apparently: he scrapes the note M wrote out of the doorframe, opens it, and disappears. What few words might have released him? Where has he gone?

Nonlinear narratives can be difficult to construct within the confines of a feature-length film, but puzzlebox storytelling has become an increasingly common feature of prestige television. Consider the recent TV hit Station Eleven, an HBO series based on Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel of the same name, which explores the world after a flu with a 99% mortality rate has decimated the global population. It contains multiple storylines, and the past and present parallel each other, intermittently converging. The show shares some other traits with A Ghost Story: striking cinematography, slow pacing, long shots, pregnant quiet. Though it’s premised on a pandemic, Station Eleven only offers snippets of the initial wave of illness; like A Ghost Story, it focuses on the aftermath. One of the major plot lines in Station Eleven follows the Traveling Symphony, an eclectic group of nomadic thespians who put on Shakespeare plays — certainly a frivolity in an unstable, post-apocalyptic landscape. Or is it?

One of the most memorable parts of A Ghost Story is a grating monologue delivered by a man — played, quite fittingly, by musician Will Oldham — at a party in the house that used to be C’s and M’s. Lowery said he wrote the monologue spontaneously long before he made the movie, but thought it added dimension to the ideas he was exploring in A Ghost Story. “It redefines what the movie is actually about: dealing with the passage of time and reconciling oneself to the inevitability of that,” Lowery explained. With so little dialogue in the movie as a whole, the message feels jarring, even pedantic. It’s too on the nose — but that’s the point. “That’s a very simple and universal concept, but one that is still so complex and troublesome, you can wrap up every single emotion in that.” Maybe that’s what makes it difficult to hear so directly. “Your kids are gonna die,” Monologue Man says, pointing past C to some party guests. “Yours too, yours too.”

Indeed, time is lost in both Station Eleven and A Ghost Story, as loved ones are dying, gone away. It’s in this darkness and confusion, amid death and destruction, that levity, creativity, and love, become urgent. As the city of Chicago is freezing over and its inhabitants dying off in the early days of Station Eleven’s flu, nine-year old Kirsten (Matilda Lawler) writes her own play and insists her quarantine “family,” a man she met at a play and his brother, perform it before they leave the apartment they’ve been barricaded in for months. Near the end of A Ghost Story, M puts on headphones and listens to the song that C was working on before he died. There are flashbacks to C in the flesh, making music, the couple loving and fighting. Redemption — life after death, in the truest sense — can be found in the littlest details and remnants, like the note M left under the paint. C is never really gone until the movie is over. Ultimately, the philosophy of A Ghost Story is life-affirming. It’s much more Casper than it is Poltergeist, and it’s a haunting well-suited to the present moment.

Read Next

About The Author